Are Green Parties More Common In High-Income Democracies?

Encyclopedia: Democracy, Elections, Civic Engagement

"This is the chance of a lifetime for us to move towards a more just, a more inclusive society. We believe it can be done. The choice is yours. If we want different outcomes, then we need to make different choices."

- Annamie Paul, Canadian Green Party Leader

The 2021 German federal elections were transformative for a number of reasons. Angela Merkel opted to retire after her impressive sixteen year tenure as Chancellor, and polling suggested that the race to be her successor was very tight between the Christian Democratic Union’s Armin Laschet and the Social Democratic Party’s Scholz. The Social Democrats narrowly got a higher percentage of the vote, but still fell considerably short of a legislative majority on their own. However, the Green Party, once a marginal protest party, put up its best showing in history, winning 14.8% of the national vote and an unprecedented 118 seats in the Bundestag. Ultimately, the Greens played the role of kingmaker, and supported Scholz for Chancellor in exchange for several ministerial positions. This example underscores a broader trend in Europe and abroad: green parties, which were once seen as an afterthought in electoral politics, are becoming increasingly popular. Their electoral popularity translates into concrete policy on climate issues, and gives voters concerned about global warming an institutional outlet to express their desire for reform.

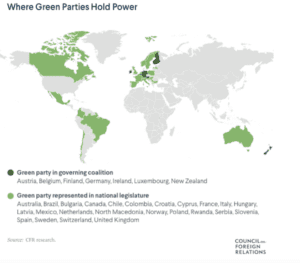

However, this renaissance of green politics is not being felt evenly across the world. Of the thirty one countries that had green party representation in their national legislatures, all but seven were highly developed OECD member states, and only eight were located outside of Europe.[1][2] Why might these high-income predominantly western countries be more predisposed to have successful green parties?

In this case study you will evaluate datasets from the DemCap Analytics tool to determine whether a country’s material wealth contributes to green party formation and electoral success. Additionally, you will consider what aspects of a high-income democracy might make green parties appealing, what responsibilities high and low-income democracies have in combating climate change, and whether democratic decision-making leads to the best climate policies. Collectively, these questions will give you a better understanding about how political values and ideology are constructed in a capitalist democratic society.

Green Parties: History and Definition

Green parties developed organically out of grassroots climate activism in the late 1960s. Industrial societies around the world were experiencing unprecedented social upheaval as the so-called “New Left” fought for a radical reimagining of global economics that existed in harmony with nature.[4]However, at first these groups were external interest groups or disparate networks of activists. They would lobby governments to enact policy changes, though they were not actively contesting elections as candidates. That changed in 1972, after the first ecologically-oriented parties were formed in New Zealand (Values Party), Australia (United Tasmania Group), and the United Kingdom (PEOPLE Party).[5] Initially regarded as protest parties, Greens have since cemented themselves as a political force. As of May 5, 2022, green parties have representation in the national legislatures of thirty one countries, and are part of the governing coalitions in seven.[6]

Green parties have evolved dramatically over time, from groups of loosely organized environmental activists into an international network of political actors unified behind a set of established principles. But what exactly are these principles? Though green parties are principally concerned with environmental issues, most green parties are not single-issue parties, and can bring a number of oft-ignored political issues such as “pacifism, human rights, and radical democracy” into policy debates.[7] A German Green Party conference after the 1979 election codified the so-called “four pillars” of green politics that serve as a common party platform: ecological sustainability, grassroots democracy, social justice, and nonviolence.[8] Although Green parties worldwide may share foundational policy stances, variations do exist between countries. Greens typically advocate for robust policies addressing economic and social problems, emphasizing the interconnected nature of these issues to climate and environmental injustice. These policies may include opposing cuts in government spending, regulating businesses, implementing progressive taxation, and supporting social safety net programs.[12]

Climate Policy

Numerous countries and international organizations are compelled to formulate climate policies and agreements to mitigate climate change effects, transitioning to and promoting renewable energy and sustainable practices. The principal concern and appeal of Green parties lie in enacting such policies to combat climate change. Climate change is propelled by the accumulation of greenhouse gasses, such as carbon dioxide, in the Earth’s atmosphere, accelerated by the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial processes. Consequences encompass more frequent and severe weather events, rising sea levels, disrupted ecosystems, and displacement, among other effects.[11] Common climate policies championed by green parties include disinvesting from the fossil fuel industry, increasing subsidies for renewable energy, promoting sustainable practices, and supporting an international response to climate change.

Democracy and Governance

Election processes and governance structures significantly influence the emergence and success of green parties. Proportional representation election systems create a favorable environment for smaller parties, such as Green Parties, by avoiding winner-takes-all election dynamics. Furthermore, countries with lower electoral thresholds foster a more diverse political landscape, enabling niche parties like the Greens to participate meaningfully. Majoritarian systems, like the one in the United States, pose significant challenges for smaller parties to secure seats in legislative bodies and executive appointments. In addition to proportional representation electoral systems, governance structures more conducive to political coalition-building provide Green Parties with opportunities to shape policies, even in the absence of a majority. A decentralization of authority also enables Green Parties to advocate for and achieve success in local spheres, even in countries in which their national impact is limited.

Materialist and Postmaterialist Values: How Economic Security Affects Values

Ronald Inglehart suggests that sustained economic stability over an extended period may result in a shift in generational values and political preferences. This shift would prioritize autonomy, self-expression, and individual rights over a primary focus on material security. Based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Inglehart argues that after basic “physiological and physical needs” are met that people can shift their attention to “higher-order intellectual, social, and ascetic needs.”[9] For instance, if during their formative years someone experiences prolonged periods of war, famine, or economic turmoil, then they would likely prioritize material stability over other values. However, when individuals grow up in an environment devoid of material scarcity or immediate survival threats, their attention is likely to turn towards post-material political concerns. These concerns include issues such as the environment, women’s rights, civil rights, sexuality, and anti-nuclear energy.

Consider the post-World War II American generation as an illustration. Raised in an era of unparalleled economic prosperity, they experienced a socialization process where basic needs like shelter, food, and security were readily met. Without any immediate economic needs, their policy priorities deemphasized so-called “kitchen table issues” in favor of zero-growth,environmental, and anti-nuclear activism.[10] This focus shift helps explain the emergence of America’s activist “New Left” in the 1960s and 1970s, as the baby boomers’ life of relative economic comfort allowed them to focus their concern on other issues. Importantly, there is a time lag associated with this value change. Conditions in one’s preadult years are integral in shaping their values, while subsequent events have a more muted effect on one’s political priorities.

The emergence of green parties within a country could be explained by the interplay between materialist and postmaterialist values. In societies with materialist values, environmental concerns may take a back seat to more pressing economic issues. Conversely in postmaterialist societies as individuals feel more secure in their basic needs, they shift their focus towards higher-order priorities, including environmental sustainability and climate change. The emergence of these parties is likely catalyzed by a population that has the luxury of contemplating issues beyond mere survival, and have the capacity to endure the short term costs associated with climate mitigation policy. However, the establishment and success of green parties in authoritarian countries, much like other political activism, is extremely difficult, regardless of the the realization of postmaterialist values. Activists in these countries face significant challenges due to constrained political space and the suppression of dissent.

Assignment

- Use the Data Analytics tool to look at the GDP per capita and Income per capita rankings for the seven countries with Greens in a governing coalition (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, and New Zealand). What do you notice? Do these countries appear comparatively wealthy?

- Explore some other features of these countries. How strong are these countries’ democracies (Democracy Index)? Can you identify any commonalities in their election systems or political institutions?

- Are there any countries with a successful green party that surprised you? Any countries without a successful green party that you expected to have one?

- Given your preliminary investigation, to what extent do you believe that postmaterialist values are the primary cause of green party electoral success in high-income countries?

- What are the potential implications of the conditions under which green parties experience electoral success?

- In the context of combating climate change, what responsibilities do high-income democracies bear compared to low-income countries?

- How does where green parties are prevalent contribute to our understanding of how political values and ideology are constructed within a capitalist democratic society?

Notes

[1] “List of OECD Member Countries – Ratification of the Convention on the OECD.” List of OECD Member countries – Ratification of the Convention on the OECD. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/about/document/ratification-oecd-convention.htm.

[2] McBride, James. “How Green-Party Success Is Reshaping Global Politics,” Council on Foreign Relations (Council on Foreign Relations), accessed March 17, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/how-green-party-success-reshaping-global-politics.

[3] Inglehart, Ronald. “The silent revolution in Europe: Intergenerational change in post-industrial societies.” American political science review 65, no. 4 (1971): 991.

[4] Tranter, Bruce, and Mark Western. “The influence of Green parties on postmaterialist values.” The British journal of sociology 60, no. 1 (2009): 146.

[5] Inglehart, Ronald. “Post-Materialism in an Environment of Insecurity.” The American Political Science Review 75, no. 4 (1981): 880–900. https://doi.org/10.2307/1962290.

[6] “How Green-Party Success Is Reshaping Global Politics,” Council on Foreign Relations (Council on Foreign Relations), accessed March 17, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/how-green-party-success-reshaping-global-politics.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Van Haute, Emilie, ed. Green parties in Europe. London: Routledge, (2016): 316.

[10] Voigt, Wolfgang. “Gründungsparteitag Der Grünen 1980 in Karlsruhe: ‘Das War Eine Ziemlich Schwere Geburt.’” Badische Neueste Nachrichten, July 24, 2020. https://bnn.de/karlsruhe/gruendungsparteitag-der-gruenen-1980-in-karlsruhe-das-war-eine-ziemlich-schwere-geburt.

[11] European Commission on Climate Change. “Consequences of climate change.” Climate Action, European Union, 2023, https://climate.ec.europa.eu/climate-change/consequences-climate-change_en. Accessed 13 November 2023.

[12] Lok Wu, Tin. “The Rising Popularity of Green Political Party Beliefs.” Earth.Org, 4 March 2022, https://earth.org/green-political-party-beliefs/. Accessed 13 November 2023.